Southwest Pottery: Ancient Traditions and Contemporary Innovations

- Laurie Seban

- Jun 3, 2019

- 13 min read

Updated: Feb 20, 2024

Overview of the creations, regional variations, and 20th century innovations of various Southwest Pueblo potters, based on the collection of the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento.

The Southwestern region of the United States is an open book of geologic time. Rivers and canyons trace through a land marked with mesas and fantastic rock formations that change with every turn. This area, called the "Four Corners" (the only place in the U.S. that 4 states meet), is rich with history.

The Southwest landscape has also been indelibly marked by some of the earliest peoples of North America. The Ancestral Pueblo peoples, or Hisatoinom (Tewa for “ancient ancestors”), first appeared in the Southwest over 10,000 years ago. The "ancients" still inhabit Horseshoe Canyon, one of the oldest sites in the United States.

Horseshoe Canyon, Utah (c. 7000 BCE)

One can still see traces of those early lives in places like Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde and Canyon de Chelly. Puebloes with stepped, flat roofed buildings, plazas, and circular ceremonial kivas were carved into cliffs and canyons.

Using extensive trade networks and sophisticated irrigation techniques, Pueblo communities cultivated the “Three Sisters” of corn, beans, and squash, tracing miles of irrigation lines across the desert floor. They flourished until roughly 1400 CE, when the people depopulated sites and melted back into the landscape.

Mesa Verde, Colorado c. 1400 CE

Today, their descendants comprise nineteen distinct pueblos and carry on the traditions of their ancestors. Each pueblo (identified by boldface here) still recalls the ancient stories of the first people emerging from the underground and still dance as embodiments of spirits from the mountains who are responsible for rainfall, fertility, and all the other blessings of life.

Pueblo potters from all different puebloes (Acoma, Cochiti, Hopi, Laguna, Nambe, Santa Clara, Santo Domingo, San Ildefonso, Taos, Zia, Zuni are discussed here) have continued the tradition of pottery as prayers that connect the ancient to the new, and three dimensional reflections of an evolving landscape.

Clay from Mother Earth is the source of Southwest pottery, and the process of creation is itself a ceremony. Each potter has their own site, often passed down from family members from which they gather clay. Like all things from nature, clay is a living entity, and each potter gives thanks in their own way for that gift.

The chemical composition of the clay reflects the distinct geography of every pueblo. In Arizona, the Hopi mine a light gray clay that transforms to buff in firing, and is the hallmark of all their vessels. The Acoma and Zuni of New Mexico use a kaolin rich clay that allows for strong, thin-walled vessels. Neighboring pueblos like Laguna, Santo Domingo and Zia have a similar clay with slightly different mineral makeup. Further north, along the Rio Grande, a dense, iron-rich clay is used in Santa Clara and San Ildefonso.

Though the clay changes, the process of creation is the same. Once the clay is gathered, it’s soaked to remove impurities, then sieved, pounded, refined and rested over a process of months to distill the clay into its purest form. To reduce shrinkage while drying, the clay is tempered with other materials like sand or stone; often, ancient shards are pulverized and added in, literally folding history into the new vessel.

Most vessels large or small start with a small disc around which rolls of clay are coiled to make a vessel. As the walls rise, they are paddled smooth and left to dry before a new section is added. Once clay hardens to a “leather-dry” state, vessels are painted with natural paint or liquid clay (slip). Colors vary according to the region and mineral content: white, brown, rust, orange, black.

Maria Martinez (San Ildefonso Pueblo) coiling clay

Forms follow functions. Vessels with stepped edges that resembled the puebloes and rain clouds were used to hold ceremonial offerings. High-shouldered jars (“ollas”) or double-spouted canteens stored water, while flattened ovoid seed pots with small openings preserved seeds.

Offering bowl, olla, canteen, seed jar

Images are painted directly onto the body using a yucca brush. Most convey hope for rainfall and fertility in a desert world: plants, birds, clouds, and rainbows form graceful patterns across the vessel.

Regional aesthetics emerge on neck and belly designs. Hopi pots trace kachinas, birds, and bears in complex curvilinear designs, with the visual focus on the flattened tops. At Laguna, Santo Domingo and Zia puebloes, polychrome pots of white, black and orange bring birds, flowers and rainbows to life. Dragonflies, like those seen on the carved Santa Clara pot below, are also symbols of water and therefore fertility.

Southwest pottery at the Crocker: Zia, Laguna, Santa Clara pueblo pottery in front

Desert animals leap across Zuni vessels, often with a “spirit-line” to convey the breath of life inherent in all living things. In Zuni, there is a preference for spare asymmetry, divided by heavy black lines and the potter’s onane, or broken line, at the neck. Stepped cloud motifs with lightning bands, feather plumes, and a variety of geometric curves complete the composition.

Zuni Olla

At Acoma, a similar style is combined in all over designs filled in with cross-hatched lines. Look closely at the eye numbing black and white patterns and you’ll see abstract renditions of corn fields, squash blossoms or rain clouds.

Acoma: Marie Zieu Chino vessel, Carrie Chino Charlie olla, JoAnn Chino Garcia vessel 1991

On San Ildefonso and Santa Clara pots, the ancient avanyu, “water dragons” that bring luck, peace and prosperity to the Pueblo people also sanctify the vessels, visual reminders of water as a sacred source of life in the harsh desert environment. They are identified by their long serpent bodies that often encircle the pot, with horned heads and an arrow-tongue that extends outwards, like a flash of lightning.

Margaret Tafoya (Santa Clara) Avanyu pot nd

At San Ildefonso, feathers or geometricized clouds often form patterns across the heavy thick walled pots. Because birds fly into the sky, and clouds in the sky bring rain, both are also emblematic of the importance of rainfall and fertility.

Erik Fender (San Ildefonso) Water Jar (olla) Eagle Feather Design c. 2014

After painting, the entire vessel is painstakingly polished with a river rock to smooth the surface. Depending on the expertise of the potter, the result is a matte surface, dull gleam or high sheen. Once again, the potter returns to the earth to be fired in-ground pits for an hours-long process of outdoor firing in which the fire must be fed constantly. The temperature must remain consistent, no small feat in an area known for sudden changes in weather. Once fired, the pots are cooled and often ritually “fed” a pinch of cornmeal to acknowledge the gift from nature. This is the same process that is carefully followed today--virtually all the Pueblo pots on display here are fired in-ground.

In the later 19th century; the physical and cultural landscape of the Southwest weathered enormous changes as tourists and academics began to visit.

Potters began to sell their wares to outside their puebloes, adapting their designs for the commercial market. With the introduction of the Santa Fe Railroad, even more buyers flooded the region--and more changes were made to traditional pottery.

Southwest pueblo potters at Santa Fe railroad stop

The Hopi potter Nampeyo was one of the first to work with American archaeologists. Using the distinctive honey clay of her Pueblo, she created designs reflecting her changing world. An early pot shows her rendition of the Catholic mission churches that were beginning to dominate

Later, studying ancient Sityatki designs uncovered by Southwest archaeologists, transferred the intricate parabolic patterns of bear claws, bird wings and other natural phenomena to her own golden hued vessels. On one small pot, bird wings beat across a central band, mimicking the migration which gives the pattern its name. The flattened oval of a seed jar frames four feathered circles on a white ground.

Hopi Pueblo: Nampeyo olla with bird migration pattern, Seed jar c. 1905,

San Ildefonso Pueblo is renowned for its black-on-black pots thanks to Maria and Julian Martinez. The married couple collaborated, with Maria forming the pots, and Julian painting the designs; an early pot shows Julian's distinctive designs on the reddish San Ildefonso wares.

San Ildefonso: Maria & Julian Martinez Jar c. 1915, Bowl with Checkerboard & Kiva Step Designs b. 1930

But they also forged new designs using old techniques. In the late 1910s, Julian and Maria began to experiment, using blackened pots that had been found at archaeological sites as models. They finally achieved their own black-on-black creations through a process of firing, using reduced oxygen conditions that drew the iron in the clay to the surface, with the red clay blooming into a lustrous black. Maria formed the pots; the elegant images painted on by Julian were then polished to perfection by Maria and fired in a kiln smothered with cow chips.

Around the same time in the neighboring Santa Clara pueblo, Sarafina and her daughters Margaret Tafoya and Christina Naranjo used the same clay and firing process to new effect; they deftly carved into the thick walls of the vessels, creating beautifully sculpted and burnished works in red (the original color of the clay) or black (reduction firing). Compare Margaret’s more sedate avanyu /water dragon encircling a burnished blackened pot to Christina’s high contrast avanyu which leaps from the belly of a perfectly carved red pot with its arrow-tongue extending outwards.

Santa Clara: Margaret Tofaoya, Jar with Avanyu. Christina Tafoya, Jar with Avanyu

And keep in mind both pots are made from the same clay! The only difference is that the black wares are fired in reducing conditions (the oxygen removed from the kiln), while the traditional red wares are fired under normal kiln conditions.

Potters today are the descendants of early potters—new branches on an ancient family tree, each with a distinct style of pottery. As part of that history, they still hew to the same process: collecting clay from local (and still secret) sites, refining, building, painting and polishing the clay before it returns to the earth one last time for firing. While their predecessors sold pots at roadside and railway stands or trading posts, today’s potters create for Indian Market and museum collections. Patterns and designs are recombined, often with new materials and contemporary motifs.

The same patterns can nourish a family tradition for over a century. A granddaughter of Nampeyo, Tonita Hamilton Nampeyo, put it best: “I want to continue the traditional methods and designs. I don’t want to deviate from what my mom and grandmother did and hand it down to the young ones. That’s the most important thing, to keep the tradition alive.”

Hopi Pueblo

On the pots of Nampmpeyo descendants, flocks of birds still take flight, echoing the ancient Sityatki forms of their matriarch (the Nampeyo family has recently

tried to copyright the Sityatki designs). A pot by Priscilla Namingha Nampeyo mimics the same bird-migration motif seen in her great-grandmother Nampeyo’s smaller version. Next door, Rachel Namingha Nampeyo uses longer, leaner lines to honor her grandmother’s designs.

Hopi: Priscilla Namingha Nampeyo bowls nd Rachel Namingha Nampeyo Olla with Traditional Bird Migration Pattern 1962

Kachina spirits still dance around the openings of Mark Tabho's seed jars. The geometric forms contrast beautifully with the variations in the distinctive golden clay of Hopi Pueblo. Unlike other vessels, seed jars are best viewed from above.

Mark Tabho Seed Jar 1992

Dextra Quotskuyva Nampeyo creates a seed jar incorporating the pottery patterns from the countless pottery sherds found scattered across the Southwest. Ancient potsherds --and new archaeological sites --are still being discovered today.

Hopi: Dextra Quotskuyva Nampeyo Sherd Pot nd

The Quotskuyvas and Youvellas, two different branches of the Nampeyo family tree, favor ivory wares that are the color of cornsilk. Originally, each one distilled single motifs (corn, bird wing or dancer) using a repousse technique to push and mold clay from the interior of a still wet pot. Today, Al also recreates elaborate scenes of the Southwest landscape on his vessels--still using the same technique!

Hopi-Tewa: Al Qöyawayma Vessels nd, 1994

The great-great grandson of Nampeyo, Les Namingha, uses acrylic paint to interpet Sityatki, Australian, Pop, or abstract expressionist styles; his contemporary pots become canvases of global cultures.

Hopi: Les Namingha, Golden Pot with Oval Opening 2011

Acoma Pueblo

Acoma potters also keep many of the ancestral Pueblo designs alive. Still using a yucca brush, Dorothy Torivio and Rebecca Lucario directly paints black and white designs that blossom and shrink in perfect syncopation with the rounded form. As with theirr foremothers, the entire design is conceived and executed from a mental template.

Acoma: Dorothy Torivio Olla nd. Rebecca Lucario Seed Jar with Geometric Designs 2011

Cerno family pots bring the natural world to life with polychrome patterns of black, white and orange interspersed with hatched and cross-hatched designs. On Barbara Cerno’s pots, a minuscule world of insects, lizards, fish and turtles swarm around small pots whose single hole (necessary to let heat escape during firing) is almost impossible to find. Can you find the air hole on the top?

Acoma: Barbara Cerno Seed Pot with Turtles, Fish and Lizards 2012

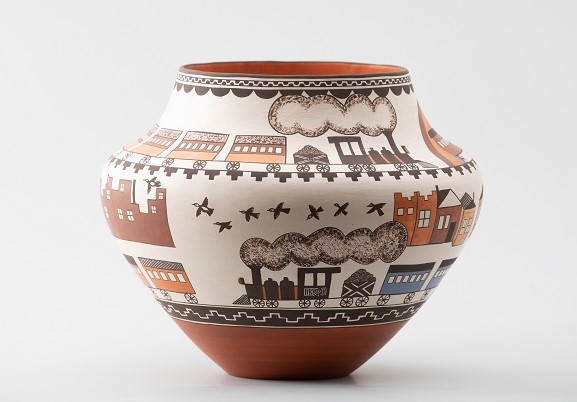

On Barbara's son Joe Jr’s massive dough pots (over three feet high and still fired in earthen pits), birds flounce their tails and deer make a path along curving patterns with hatched lines. In other cases, trains do.

Acoma Pueblo: Joe Cerno Jr. Olla with Deer and Bird 2011, Barbara & Joe Cerna, Pictorial Train Olla, 2011

San Ildefonso Pueblo

San Ildefonso: Maria and Julian Martinez feather plume pot nd, Gavan Gonzales jar nd

Family looms large in San Ildefonso as well. The feather plume design of Julian still radiates around a bowl, perfectly formed and polished to perfection by Maria. Another plate shows the same design as interpreted by Maria and Julian’s son, Popovi Da, who collaborated with Maria after the death of his father. Gavan Gonzales echoes his great great grandparents work.

San Ildefonso: Popovi Da pots. Barbara Gonzales Seed Jar nd

Popovi was the first to inset stones into clay, and create a shallow sgraffito carving on the surface of the vessels. After his death, his son Tony Da worked with Maria, creating some of the first red/black vessels.

Santa Clara Pueblo

At Santa Clara pueblo, an enormous proportion of the population continues the tradition of ceramics today. The spirit line emanating from the mouth of the avanyu becomes the focus on the pot of Sherry Tafoya, granddaughter of Christina Naranjo.

Sherry Tafoya, Dragonfly pot

Tammy Garcia, great-great-granddaughter of Christina Naranjo, also transforms clay into new forms: pots, cubes, columns, all carved with sharp recessed designs that echo the past in unusual ways. Familiar forms like birds and feathers are cut out in sharp relief. Curved shapes that echo the form contrast with sharp angles (sometimes punctuated with metal or stone inlay). Garcia actually replicates traditional clay forms in silver, bronze or glass in a prodigious variety of forms.

Tammy Garcia Northwest Coast pot

As modern as the forms may appear, for the potters, the importance is their reference to the past. According to Margaret’s grandson Nathan Youngblood, “The way we do our pots, the traditional way, was the way that was handed to us by the spirits that came before us. In order to show the proper respect for the clay and to the clay we need to continue doing it the old way, and that means digging your own clays and mixing them together, hand coiling, hand burnishing and outdoor firing.”

Santa Clara: Nathan Youngblood Carved Black Egg 1988 Nancy Youngblood Vessel

Using that traditional method, his family (including sister Nancy) makes strikingly modern, exquisitely sculpted pots in the iconic red or black colors. They recall the older melon pots, but with sharply recessed ridges that catch the light (and are the only pots here that require firing in an electric kiln). Helen Shupla, another Santa Clara potter, does the same form.

Helen Shupla (Santa Clara) Melon Bowl nd

The sgraffito technique of etching into the clay also provides new avenues of creative inspiration. Jody Naranjo uses the technique on her Pueblo Girls, ancient dancers brought into the contemporary world—but she uses a river stone “that still bears the handprints of her great-grandmother and grandmother” and keeps tradition alive by translating it to textiles, bronze, and glass.

Jody Naranjo (Santa Clara), Large Square Jar with 194 Figures, 2003

In the Pueblo world, the first humans emerge from the ground. One thinks they might have resembled Roxanne Swentzell’s figures: short squat smiling figures filled with life. Her people recall the ancient stories: emergence into the world, the potters and home-makers, the storytellers, and the black and white koshare--sacred clowns whose duty is to entertain and educate. They all have an earthy sense of humor. Toe Jam memorializes the most mundane of acts. In Swentzell’s work, as with the rest of the clay, the earth comes to life and speaks to us once again.

Santa Clara: Roxanne Swentzell, Toe Jam Looking for Root Rot 2004

Nambe Pueblo

Nambe: Lonnie Vigil, Jar, nd Robert Vigil, Jar with Avanyu 2016

Nambe and Taos pueblos are both known for their micaeous clay; the mica in the clay creates vessels that glint in the sunlight, and are much more heat tolerant. As a result, there is very little surface decoration. Robery Vigil adds the avanyu for an added measure of beauty (and good luck).

Cochiti Pueblo

Ultimately, Southwest potters are storytellers in three dimensions. No potter illustrates this better than Helen Cordero of Cochiti Pueblo, who began adding small figures to her clay pieces in the 1960's, a memory of children listening to the stories of the elders when she was young. Today, storyteller figures are a ubiquitous presence in Southwest tourism, with all sorts of creatures listening in rapt attention to the words of their ancestors.

Cochiti: Helen Cordero Storyeller, nd. Diego Romero, A True Tale, 2005

Diego Romero chooses to tell a different story--one perhaps more critical of the history of Europeans as they entered the Southwest, but no less true. This plate illustrates the consequences of the 1599 Acoma Revolt: when the conquistador Onate managed to retake the pueblo, he ordered the right hand of each Acoma male to be cut off as punishment.

San Felipe

Other contemporary artists revise the idea of a pot itself! When looking at Hubert Candelario's pot, remember that the vessel is still formed with soft clay!

Hubert Candelario, Jar 2012

Throughout the galleries, other media from Southwest artists are also showcased.

Many Pueblo artists, for example, have moved beyond clay to use other forms as a means of reflecting their culture. Another Namingha of the Nampeyo family, Dan, paints the landscape the Hopi inhabit in saturated colors, recalling the ancient pueblos and ageless mesas. And Dan’s son Arlo re- the spirits that still dance across those spaces, in abstract wood and metal forms, contemporary versions of the kachinas his great-grandmother once created.

Hopi: Michael Naimngha, Arlo Namingha, Cultural Images #3 2004

And the neighboring Navajo, an entirely separate group of people that also inhabit the Four Corners region, have added their talents to the pottery market. The Begay family melds their Santa Clara and Navajo traditions together with red pots carved into complex abstract designs that honor the Pueblo kachinas and also the Navajo ancestral spirits, or Yei. Samuel Manymules use a local micaeous clay to create melon pots. Lorraine Williams, another Navajo, also honors the yei .

Santa Clara/Navajo: Harrison Begay Jr. Jar 2000. Daniel Begay Jar 2010

Navajo: Samuel Manymules Melon pot nd Lorraine William, Ancestral Jar

IMPORTANT: When buying Southwest ceramics, make sure to buy Pueblo arts from actual Pueblo artists! keep in mind that Pueblo potters sign their pots WITH their pueblo. Navajo potters will sign their name. Anything signed with the term "----style" means that it was not done by an indigenous artist--so make sure to support indigenous artists and look for the signature.

Resources:

Native America Ceramics at the Crocker: https://www.crockerart.org/collections/pueblo-dynasties-master-potters-from-matriarchs-to-contemporaries?page=2

Jody Naranjo on making pottery: http://www.santafenewmexican.com/pasatiempo/art/walking-with-her-ancestors-ceramist-jody-naranjo/article_1988c576-259f-559d-b73b-7971761eefa7.html