California Basketry: Woven Landscapes

- Laurie Seban

- Aug 13, 2020

- 8 min read

Updated: Apr 1, 2024

Although basketry is a global art form, native California basketmakers wove with an unparalleled variety and virtuosity, creating exquisite vessels that served a utilitarian and sacred purpose, a metonym for native California cultures.

The earliest archaeological evidence of California cultures dates to 11,000 BCE. By the historic period, the state’s varied geography (coastline, deserts, plateaus, wetlands, grasslands, foothills and mountains) was matched by the diversity and density of its communities: over 150 distinct groups with more than 100 different languages spoken. They coexisted in a network of smaller scale tribelets that traded for goods across the state.

While each group was distinct, some common themes prevailed. Groups subsisted by hunting and careful cultivation of local plants. As one California native botanist put it, “California was a garden of Eden because we made it that way.” The acorn was a staple crop for most Californians, and many of the oak groves and diverse flora throughout the state are a product of that early maintenance. Stands of grass were propagated for seed, other plants for their fruits, and still others for their roots.

Land worked for generations also produced an abundance of basketry materials. Succulents, grasses, roots, shoots, and branches were transformed into tools for living, ranging from impossibly small medicine baskets to massive burden baskets. Nets and different types of traps were woven by men while baskets for food collection, preparation, storage were usually woven by women.

Jennie Miller (Pomo) with burden basket/Pomo burden basket

Large triangular burden baskets are some of the most spectacular products of

California culture; women across the state used this iconic form to carry grasses, seeds, nuts, and branches on their backs. Depending on the specific area, baskets like these could be made from combinations of redbud, willow, sumac, pine, sedge, or bear grass.

Every basket represented a distinct relationship between weaver and environment, a form of respect and reciprocity common to most indigenous cultures. All weavers had specific sites, with their own means of acknowledging nature at various points. Cultivation, maintenance and gathering of plants required intimate knowledge of each plant; sites would be visited at different points over the season to aerate roots, prune, or harvest at different points. Some basket materials required new growth, some old. Some plants might be collected and used immediately, others left to cure. Weavers trimmed materials to correct length, then split, soaked and dyed them. In all, the process of preparation took at least as much time as the weaving itself (if not more).

And weaving itself was undertaken with utmost concentration and respect: each basket was seen as a prayer in itself, a sacred pact between weaver and the world. Certain rules and restrictions were observed in the times one could weave and during the process of weaving itself.

Basketry techniques were distinct to the region, learned over time through aiding and observing elders. In Northern and Central California, twined baskets like the burden basket above were a product of horizontal wefts threaded through a foundation of radiating warps. The overall effect is that of woven cloth, with multi-colored plant materials woven into the basket itself to form patterns, or wrapped around the wefts to form a multitude of complex designs.

Coiled baskets from Central and Southern California required groups of rods that were coiled around a basketry “start,” then stitched together.

Yokuts women weaving a coiled basket Yokuts coiled baskets

Design elements were wrapped around the individual coils. The overall effect is a series of horizontal coils that wrap around the vessel.

Twined baskets were created by extending a series of warps from the basketry start; wefts were then woven through, creating a woven effect similar to that of cloth.

Twined Yurok/Karuk Hupa cooking basket /Twined Konkow feasting basket c. 1900

Both twined or coiled cooking and feasting baskets were so tightly woven, they could hold liquids for several days.

Plant materials were generally determined by the region, though a single basket could contain plants traded from several different areas. Certain patterns and motifs might also be common to a geographic location. Triangles, for example, figure prominently in the Northwestern groups of California (Yurok, Karuk, Hupa, Wiyot), while horizontal and vertical zig zags enliven many central California baskets.

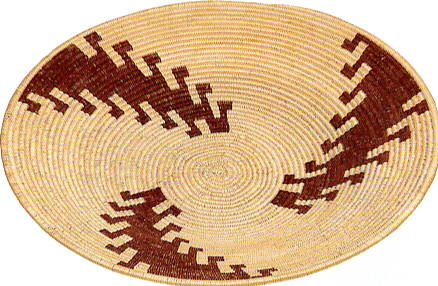

Yurok/Karuk/Hupa cooking basket/Guadalupe Arenas (Cahuilla) coiled tray c.1910/Bertha Mitchell (Wintun) coiled winnowing tray

The plants, animals, and other patterns that travel across the textured surfaces were allegorical landscapes, ingenious reflections of nature in abstract form. Butterflies, water striders, frogs, lizards, snakes, fish and mammals appear as geometric motifs. Rattlesnakes coil around baskets from desert groups like the Cahuilla basket above. Bertha Mitchell's winnowing tray is decorated with what she called a "quail tops" design.

Looking at the intricate patterns, it’s clear that complex mental mathematics were required to calculate the different lengths and quantities of plants needed for evenly spaced designs (laid end-to-end, the materials for a single medium basket could reach the height of a 40 story building). In some cases, interior and exterior motifs could be entirely different. In the case of the coiled Pomo gift/storage basket below, the bands are deliberately reversed on the interior, creating a stunning contrast when viewed in its entirety.

Pomo coiled gift/storage basket c. 1840/interior

Embroidered gift baskets could be given at birth or important rites of passage.

And while this category of basket is seen across the state, central California produced some of the most exquisite gift baskets embellished with shells and feathers. A coiled Pomo basket (tapica) with a quail plume pattern is punctuated with actual quail topknots; baskets like these are a reminder of the skill of a hunter in catching the number of quails for such a basket, too!

Other Pomo baskets shimmer with iridescent feathers. A gift basket covered with meadowlark, flicker and mallard feathers, embellished further with quail topknots and shells, is of superlative quality. Clamshells discs and abalone pendants edge the rim. The feathers are on the bottom of the basket; a cordage strap was usually used so the basket could be hung and seen from below. Pomo tapica

Another name for these are “jewel” baskets, and the feathers do glisten and change with the light. They echo the appearance of the birds in nature: a bobbing topknot a quail scuttling into the bush, the gleam of emerald like mallards on the water, a glimpse of yellow marking meadowlarks in the grasses, or a red flash of flickers in the forest.

Pomo/Patwin weaver Mabel McKay (1907-1993), responsible for weaving some of the most exquisite baskets in collections today (some no smaller than a pinhead), spoke of her baskets as a gift from the spirits, a visual prayer that crystallized her relationship with the natural world.

Mabel McKay (Pomo) coiled treasure basket

Baskets often served a sacred or ceremonial purpose. Cylindrical Jump Dance baskets of the Northern California Yurok, Karuk and Hupa, for example, were created exclusively for ceremony and viewed as sacred themselves. Medicine baskets might be used in curing; though they are not often seen in collections, a “canoe” shape is often associated with this function.

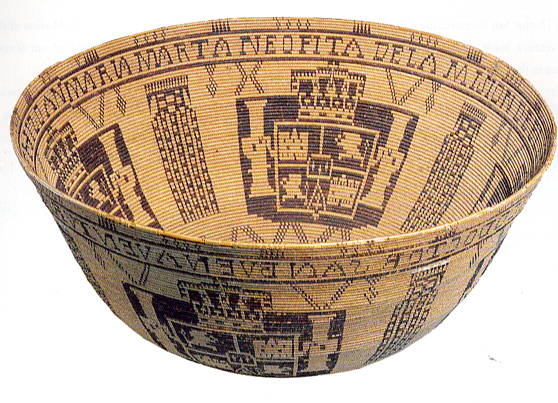

Post-contact basketry portrays a land irrevocably changed by contact, beginning with the arrival of Spaniards in Southern California during the 16th century in southern California. The introduction of diseases and brutal process of “missionization” (by which natives were conscripted to work Catholic Church lands and build the state’s mission system) wiped out whole populations by the early 19th century. Yet as early as the 1700’s, basketmakers were

adapting their wares for outsiders. On baskets woven by novices (natives in the mission system) and shipped back to Europe, Spanish coats of arms, even writing appear.

Ana Maria Marta (Chumash) Viceroy's basket early 18th century

In Central and Northern California, the government sanctioned clearing of land for ranches and gold mining in the 19th century resulted in the deaths of over 100,000 California natives between 1855 and 1865 alone. Laws were enacted across the state that awarded bounties for on native heads (almost one million dollars was paid out in the first 2 years of California statehood), allowed the indentured servitude of any unemployed native, and legalized the white "adoption"/kidnapping of native children. Remaining people were forced to work on the land-grant ranches that had supplanted their homelands, or pushed into small rancherias (rather than the larger reservations on the Plains).

By the late 1800’s, native weavers were creating innovative forms adapted to a growing market for baskets. Up north, the lidded trinket baskets of Wiyot-Karuk weaver

Elizabeth Hickox (1872- 1947) afforded her the opportunity to buy a car and travel to San Francisco on shopping trips. Even today, weavers marvel at her perfectly twined baskets of up to 500 stitches per square inch. Woven from fern and graperoot into striking diagonal patterns, each one is finished with porcupine quills and an innovative knobbed top perfectly suited to Victorian tastes at the time.

Elizabeth Hickox (Wiyot-Karuk) trinket basket

While working at a laundry near Yosemite, Carrie Bethel (1898-1974), a Mono Lake Paiute weaver, coiled tightly woven storage baskets of sedge, bracken fern and redbud, using stitching to create intricate polychrome designs. Her baskets won accolades at the Yosemite Indian Field Days and garnered high prices on the market.

Louisa Keyser (Washoe) degikup basket Carrie Bethel (Mono Lake Paiute) basket

Louisa Keyser (1831-1925), a Washoe weaver also known as Datsosalee, illustrates the complicated history of marketing basketry. Keyser wove miniature and large coiled baskets for her employers Abe and Amy Cohn, to be sold at their Tahoe and Carson City trading posts. She introduced a new form, the degikup, a rounded coiled basket with a small opening that had no precedent in historic Washoe basketry. Keyser’s technical and creative mastery is seen in the way her designs subtly expand with the basket. The spire patterns on the degikup are also an innovation, representing what she termed “beacon lights.”

Her talent was recognized early; the Cohns charged much higher prices for Keyser’s baskets, even using a separate ledger book to track their profits. Yet she was not recognized as an innovator. Instead, she was marketed as an “Indian princess” making “traditional” baskets. The degikup was given a fictional history so that it would command higher prices (buyers were told it was used in funeral rites for the “chief”). Today, however, it is both her superlative technique and artistic creativity that is prized, instead of any conformity to perceived “traditions.”

Some weavers continue to create the baskets of their ancestors and elders. Linda Aguilar

specializes in miniature baskets typical of her Chumash forebears; hers, however, are often made of horsehair, to call attention to the lack of available materials. Woven in the same traditional Chumash style with an assortment of shell pendants, they embody the reality of a 21st century California whose landscape is no longer native.

For the past few decades, access to traditional gathering grounds has been restricted by

development, and pesticide use in all areas has threatened the health of weavers. Private and public agencies are working to provide safe materials for elders and weavers, but the large baskets of the past are no longer possible simply because the quality and quantity of plant materials has been lost. Basketry continues to evolve, however, as weavers pass on their knowledge and skills to the next generation of weavers.

And nature preserves can become important sites for indigenous culture-bearers to restoe and maintain native plants for weavers. Sometimes, that includes carefully planned burns using traditional indigenous methods, as Diana Almendariz (Maidu/Patwin) does at Cache Creek Nature Preserve in Woodland.

Further reading:

Many of the baskets shown here were taken from Brian Bibby, The Fine Art of California Indian Basketry. Sacramento: Crocker Art Museum and Heyday Books, 1996.

For a historical overview, read Baldy and Middleton, Introduction to California Indian History: https://www.nativewomenscollective.org/regaliastoriescaliforniahistory.html