Contact

- Laurie Seban

- Aug 19, 2020

- 6 min read

Updated: Feb 20, 2024

What are the characteristics of a civilization—are they relative? In Western European culture and history, the markers have been literacy, religion, technology, and a cultural system that reinforces those beliefs. Today we might add in computer technology, but the basic principles haven’t changed too much over time. In the 1400’s, Europe was filled with cities, churches, palaces, sites of learning, all filled with texts, the latest technology, and various art forms reflecting those beliefs.

Ironically enough, American cities were very similar at the time! In the 1400’s, the Americas were also teeming with a wide variety of cultures, hundreds of distinct languages, and thousands of communities ranging from small-scale hunting and gathering groups to large scale civilizations. Albrecht Durer, one of the quintessential Renaissance artists, marveled at Aztec goldwork shipped to Germany; the metalworking technology was beyond European capabilities at the time. In Peru, entire gardens were made of gold and silver, and some forms of electroplating practiced by the Andean Moche still can’t be replicated today (and all the gold shipped from the Americas was melted down, so we have very few examples that survive today).

Were Meso and South American civilizations considered the equal of European civilizations at the time? We all know the answer to that –but why? The difference is in how civilization looked. Our entire Western (as in American, Western European) body of art, architecture, and literature is based on the classical ideal of beauty: naturalism, symmetry, and a beauty based on Western features and a harmony of all the parts. Literacy was based on European languages, and religion was based on the Judeo-Christian ideal.

Village of Secoton, Theodore De Bry, 1588 / The Elder Spring, Pieter Breughel, late 16th c.

The majority of the globe developed independently of Greece and Rome, with cultural beliefs and principles that were very different. Aztec and Maya codices were very different than the Bible. None of the gods looked like the Western God, or Christ. And while Inka roads were far more sophisticated than anything found in Europe, they did not have the same forms of transportation found in Europe. Nor did they have the same weapons—and the European gun trumped any indigenous defense.

During the colonial period that followed, Western culture (the common culture of Western Europe and America) looked at non-Western cultures through the prism of the West, and when the same values were not found, those “other” cultures were seen as lacking. Meanings were created according to Western desires and ideals. So even though the Native American village of Secoton was discussed as strikingly similar to any European village, the people were seen as inferior.

The best example of that is contact: when Columbus first arrived on the island of Hispaniola (now the Dominican Republic), he was searching for a new route to India; he therefore named the Taino people he found “Indians.” For Columbus, those Taino/Indians did not have Western markers of progress—they had different spiritual beliefs, speech, and structures. He therefore deemed them sub-human, which justified their control and eventual enslavement as more conquistadors with weapons flooded the New World, wreaking devastation in their path. Not only devastation caused by gunfire, dogs and mass burnings, but also the utter destruction caused by the introduction of new diseases to which natives had no natural immune response: measles, smallpox, and even the common cold. It’s estimated that between 90-97% of the indigenous population was wiped out by disease (which for Europeans was further proof that conquest was ordained by God).

Columbus’ Arrival in America The Taino Indians Spaniards Burning Arawaks John Vanderlyn 1845 Wenceslaus Hollar 1645 Bernard Las Casas 16th c.

Eventually, priests baptized the natives left behind, often conscripting them into service of the church, constructing the building, churches, and cathedrals, working their land. Cross of Thorns, a new book by Enrique Castillo, estimates Junipero Serra’s mission system drew in millions of dollars annually, all based on the labor of California natives). Conversion to Christianity also led to the destruction and loss of the customs, ceremonies, culture, artwork, and even languages—the loss of life in Southern California was so complete that up until a few years ago, they were collectively grouped under the name Mission Indians because there were so few survivors left.

As cultures were lost, the cultures were defined according to Western terms: not only as Indians, but also savages (not Christian), barbaric (because of their weapons), or sub-humans with inferior intelligence. In the case of the Aztec, all their written texts were destroyed. In the case of the Maya, it wasn’t realized that their stone stelae were actually texts until the 20th century!

And definitions could change over time: Rousseau’s 18th century ideal of the “Noble Savage” can be seen in the idea of Pocahontas as an Indian Princess, for example, or the romantic image of the Plains warrior on a horse, reinforced by Buffalo Bills Wild West Show, which travelled across the globe.

John Chapman, The Baptism of Pocahontas 1839 Buffalo Bill poster late 19th c.

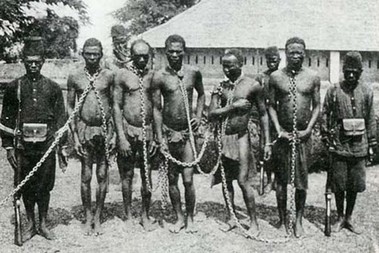

But as America expanded westward, and the European slave trade needed more slaves, those romantic ideas shifted to more dangerous ideas: Indians as scalping savages, Africans and Australians whose skulls were compared to those of Europeans and shown to be inferior in the now defunct science of “craniology.” This philosophy justified the African slave trade, responsible for moving millions of Africans across the Atlantic to work (40% in the Caribbean, 38% in Brazil, 17% in Spanish America, and 6% to North America) on the farms that fed Europe: sugar, cotton, tobacco, tea. It also justified the wholescale slaughter of California natives after the Gold Rush, and the Australian frontier wars and eventual “containment” of Australian natives.

Photograph of Congolese slaves, 19th c. Print of British slaves in Caribbean, 19th c.

The brutality increased as the global maritime trade did; by the 19th century, the slave trade had waned, but Africa was now colonized and exploited for its raw goods instead. In the Congo alone, over 10 million Congolese are estimated to have been killed under the brutal policies of King Leopold of Belgium in the first decade of the 20th century.

Transatlantic Slave Trade

Colonialism (and slavery) was justified by the International Expositions and museums of colonial countries. Expositions, which advertised the best that each European nation had to offer, exhibited subjugated peoples in pens, as they traveled with the animals from capital to capital. Museums like the British Museum the Berlin Museum, the Trocadero in Paris and the Smithsonian in Washington put bits and pieces of people on display to represent the whole. Not surprisingly, these displays usually emphasized the “wow” factor: weapons, masks, and other items the emphasized difference rather than similarity to the Westerners that visited the museums.

Musee Congo, 19th c. Bella Coola men in Germany, 1885.

Indigenous cultures became a blank canvas on which to project European fears, desires. Pocahontas as a princess, Indians as scalpers, Tahitian women as exotic fantasies, headhunters of the Pacific. Eventually, those ideas became a part of our popular culture: our art (Picasso’s 1907 Desmoiselles d’Avignon, in which masks are used, according to Picasso, in order to “shock and terrorize the viewer”), our literature (the Lone Ranger, Tarzan), and eventually movies, advertising, and even sports mascots. This concept of Primitivism permeates our culture today. Why else do we still use the term Redskins, Indians, or Braves to represent the ferocity of a football team? Or always think of Pocahontas in terms of John Smith?--especially when she married another Englishman!

Seed of the Areoi Desmoiselles d’Avignon Atlanta Braves logo

Paul Gaugin, 1892 Pablo Picasso,1907

Western culture is just learning today to value non-Western cultures on their own terms. We’ve come a long way, but some would argue not far enough; check out Binyavanga Wainaina’s cheeky response to a Taylor Swift video set in Africa with not a single African seen: only it's elephants, zebras, and European colonials. The fad of wearing feather bonnets is another example of popular culture’s appropriation of indigenous cultures (now banned at music festivals in the UK because it’s seen as culturally insensitive).

Taylor Swift, Wildest Dreams video (2015)

How do you see the heritage of Primitivism in popular culture today?P.S. I learned the proceeds of the Swift video do go 100% towards the African Parks Foundation. P.P.S. I wonder how the budget of the African Parks Foundation compares to the budgets of other foundations set up to fight AIDS, malaria, or other life-threatening illnesses in Africa.

Comments