Musee d'Orsay, Paris

- Laurie Seban

- Sep 26, 2021

- 30 min read

Updated: Jul 17, 2024

The birth of 19th century French modernism as seen through the masterpieces of the Musee d’Orsay in Paris.

The Musee d’Orsay sits on the Seine at the center of Paris. It is re-purposing at its best: a former train station transformed into a treasure of 19th century modernism.

Modernism began in cities like Paris. In the 19th century, as factories developed and large numbers of people moved to cities to work in those factories and other related jobs, a middle class of merchants and white-collar workers developed to serve the burgeoning population. By the 1860s, Paris was a city of 1.7 million, with a population looking for new leisure-time activities. Its wide boulevards lined with shops, cafes, and restaurants bustled with a new pedestrian culture. On the weekends, dance halls in Montmartre or along the Seine entertained the wage workers and the wealthy.

Trains bringing people and goods into the city, were the epitome of a new urban culture. The Gare d’Orsay was built in 1900 for the Paris Exposition Universelle as a demonstration of modern progress, with a massive central hall enclosed in iron and glass. In 1939, the rail station closed.

Monet, Gare St. Lazare 1877

In 1986, the Orsay (D'O, as it's called) re-opened as a museum. It’s fitting that a former train station houses the artworks which are the first to celebrate modern life (and sometimes the escape from it). Because of its unsurpassed collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist masterpieces, it is the second most popular museum in Paris (and much easier to visit than the Louvre). Think of Orsay as a station still, with various stops on the path to modernism.

Text with arrows will help navigate you through the museum and specific galleries

->The best journey is to stroll through the lower sculpture gallery in Rez-de-Chaussee (level 0), then return to the front, passing through the right hand galleries first, then crossing over to the left. This will give you an idea of traditional academic art at the beginning of the modern period, before ascending to the plein-air painting of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists in the upper galleries.

->For a quick (1-2 hour) visit, save your time for the Median level (1) galleries of Realists like Manet, Courbet and Degas, and the Impressionists like Monet, Renoir, and Cassatt. The Superieur level (2) houses Post-Impressionist works by Cezanne, Seurat, Toulouse-Lautrec, Van Gogh and Gaugin.

->A crowd of sculptures are there to greet you as you descend the steps into the museum. Filled with skylights that flood the gallery with natural light, you can see why a train station is an ideal venue to meet with art.

Academy style

The "academic" style promoted by the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, the art academy of Paris, dominates the lower gallery painting and sculptures. Graceful figures in classical robes inhabit the central hall, with paintings in the rooms on either side. As was typical for "academic" works, mythological, Biblical, or historical scenes predominated, with a few exotic locales sprinkled throughout.

First is Lady Liberty, a 3 meter version from 1889, gifted by the sculpture Frederic Bartholdi to France. Bartholdi worked on his 46 meter original from 1875-1885 with the help of Gustav Eiffel and Eugene Viollet-le-Duc (who had recently completed the renovation of Notre Dame). Bartholdi’s studio in Paris was a tourist site in its day—the colossal work, made from a steel frame beneath a copper veneer was a technological achievement only made possible with the recent invention of steel. After Liberty was shipped (in pieces) to America, Bartholdi gifted two other versions to France: the Orsay’s 3 meter version as well as an outdoor version that can be seen near the Eiffel Tower (or on Bateaux Mouche tours).

Bartholdi, Lady Liberty 1886

To give you an idea of how long-lived this academic style was for artists, Jean-Dominque Ingres’ Odalisque from 1814 reigns at the Louvre, while La Source, painted by Ingres over 50 years later, can be found at the Orsay, making him one of the few artists whose works is found in both museums. La Source displays a female nude balancing a jug of water at a spring (or “source”), like a statue come to life. Ingres was known for his “licked finish,” meaning the surface of canvas was completely smooth, with no visible brushstrokes.

Ingres, La Source 1869 Bougereau, Birth of Venus, 1863

Nudes were standard fare for Academic works, allowing the viewer to look as long as they wanted, which was exactly the point at the time! Painters like Ingres and William-Adolphe Bougereau were the most famous painters of mid 19th century Paris, known for the luscious quality of their nudes, dressed only in mythological themes. Paintings like this were meant to be a window into another world.

Bougereau’s Birth of Venus, born from seafoam, emerges from the ocean, fully formed and on display for the viewer. Emile Zola observed that she resembled "a delicious courtesan, not made of flesh and bone - that would be indecent - but of a sort of pink and white marzipan." Nudes like this, usually with eyes closed or head turned so the viewer could gaze upon the flesh without distraction, were meant to be consumed by the largely male audience.

->Lifesize nudes greet you at the far end of the museum. The Four Parts of the World , a lifesize plaster model of Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux’s bronze at the Paris Observatory,

perfectly captures the optimism of mid 19th century art, the feeling that anything is possible, with four female nudes, each representing a continent, balancing a celestial sphere—this new modern world-- as they revolve around it in a graceful dance. And while it looks very traditional and classical to us, it was originally panned by critics for its “wild, wrinkled and vulgar dancers.” The rough texture and elongation of the figures offended a public accustomed to the smooth serene nudes of academic sculpture which now surround it. See if you can recognize each continent by its (perceived) characteristics: Europe, Asia, America with a feather headdress, and Africa, with broken shackles at her feet.

Carpeaux: Four Parts of the World 1872

Carpeaux’s towering stone Danse, originally created for the façade of the Paris Opera, was even more scandalous. Three female nudes encircle a male—a common classical motif. Perhaps it was the positioning of the figures, the rough, almost expressionist handling of the bodies that made the figures too realistic. Immediately after its installation, women were warned to avoid getting too close to it, and someone attempted to “dress” it with black ink!

Carpeaux, Danse 1865-69

Even more daring: Ernest Barrias' Alligator Hunters, which portrays a "Nubian" spearing an alligator in the throat, while a woman clutching two babies looks down in terror. But what strikes the viewer is the other woman tumbling headfirst towards the viewer, as the alligator's tail flicks the floor.

Barrias, The Alligator Hunters 1894

Is it deliberate, or just ironic, that at this far end of the sculpture gallery, three “Other” African figures look across the room? Polychrome sculpture was popular in the 19th century, with different marbles used to “dress” classical style figures. Charles Cordier, a specialist of so-called “ethnographic subjects,” travelled to Algiers, Egypt and Greece, using the stones from each in his works to create portraits of the people there. His three heads in onyx and bronze are especially striking. The onyx used for the clothing and base was quarried in Algeria, which at the time, was part of France’s colonial empire.

Cordier: Arab of El Aghouat 1861 Black Woman from the Colonies 1861 Negro from Sudan 1856

The darkened bronze faces of his Algerian subjects are beautifully detailed, each one from a different area. The dramatic contrast in color gives a sense of how those subjects themselves might have felt, separated from the crowd. Cordier’s sensitive portrayal of each is a demonstration of the speech he gave to the French Society of Anthropology in 1861 which in part, said, “Beauty does not belong to a single privileged race.” A smaller bronze, Love One Another was finished at the height of the Civil War. There is no differentiation of material or race as the two young children embrace—though the Caucasian child is larger and the smaller African child is still in chains.

Cordier, Love One Another 1867

->Continue into the street side galleries of the lower level

Barbizon School

->The street side of the lower galleries are a stark contrast to the Academy fantasies, and show the growing interest in a new form of realism—not of the past, but the present. These are massive works that were intended to make a statement by celebrating the everyday. Barbizon painters were a loose group of Parisian painters that chose to paint directly from nature, in the Forest of Fontainebleau just outside Paris. As factories and cities began to swallow the countryside, these artists painted in a plein-air style, directly recording the effects of natural light on the landscape around them, using soft tones and brushstroke. Because they gathered (or lived) in the small village of Barbizon, they are called the Barbizon painters. The works of Camille Corot, Theodore Rousseau, Jean Millet, and others are at the Louvre, but also here.

Corot: Dancing Nymphs 1850 Souvenir of Mortefontaine 1864

Corot's innovation was to paint in the present: compare Dancing Nymphs to Souvenir of Motefontaine, and you can see how contemporary peasants replace mythological subjects. He used pure lead white paint (which was actually toxic) directly on the canvas; those hints of pristine white lend a sparkling air to his landscapes that are unlike any others.

Corot was also legendary in his support of the poor—and poor painters. His philosophy of painting from nature was hugely influential on the next generation of French Impressionists; Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot and especially Camille Pissarro counted him as teacher and friend. And he supported fellow Barbizon artist Jean Millet and his family even after Millet’s death.

Jean Millet specialized in the peasants themselves. The Gleaners were the poorest of the poor; without fields of their own, they gleaned the crops for any leftovers after the field had been harvested. His painting manages to make even backbreaking work beautiful: a glowing sunset, peasant women stooped over a field, gleaning the last of the crop. Think that way of life has disappeared? Think again—peasants in many parts of the world still make their living that way.

Rosa Bonheur lived in Paris, but specialized in the animals of the countryside: horse fairs, oxen, cows. As a woman, she was not allowed to do large-scale works of importance, but she did make monumental works of farm animals. Plowing in the Nivernais shows the strain of the oxen as they plow a field, tendons bulging and fur glistening. To ensure that accuracy, Bonheur petitioned the Paris police so she could trudge through the stench and blood of slaughterhouses in pants, arguing that dresses would impede her research. Bonheur was actually the first woman to receive a medal in the annual Salon competition, and so well-known that kings, queens, and even Buffalo Bill requested her animal portraits.

Realism

Honore Daumier was a caricaturist, the beginning of France’s long tradition of satire. He is best known for his cartoons, some of which are on display: a gargantuan Louis-Philippe, whose tongue is a conveyor belt for all the work of the peasants as politicians stand by. For this, he was jailed for 6 months, but after his release, he continued to critique the government.

Daumier: Gargantua 1831 Heads of politicians, 1832-35

In his long career, Daumier proved himself master of many media. On display and worth a closer look are 26 heads in clay, painted with oils. With a few deft pinches, politicians of all types (arrogant, sniveling, lazy, sleeping, grimacing) are put in their place. Only one, a fellow journalist, is simply smiling.

It is only at the end of his life that Daumier took up painting, and managed to infuse the working class with the honor he found lacking in politicians. La Blanchisseuse, though smaller than Millet’s Gleaners, is equal in the dignity which suffuses the washerwoman as she mounts the steps with her child.

Daumier, La Blanchisseuse 1863

->Realism and modernism begin in earnest with Gustave Courbet, whose works are showcased in an open gallery. Courbet was always a rebel. Born wealthy, he flouted convention at every step; by all accounts rather rude, a devout Communist (it was he who toppled the Place Vendome column in the 1848 revolution) and devoted party-goer (on occasion dressed as a woman). He rebelled against the French Academy, too, creating paintings that flouted artistic conventions.

His Burial at Ornans, depicting the funeral of his beloved grandfather, was rejected from the annual Academy Salon. Can you see why? First, it depicts everyday men in modern dress on a massive scale (10 x 20 feet). Paintings this size were normally used for history paintings--historical, Biblical, or mythological stories meant to uplift the viewer with a moralizing lesson. But here, there are no heroic figures, nor bright spots of colors or carefully planned compositions—just a series of figures in everyday dress gathered around a burial plot.

Courbet vehemently rejected the idea of mythological paintings and instead painted modern life. No togas, angels, gods or saints in Courbet’s works. “Show me an angel and I’ll paint one,” he said. Apparently there were none in his world. But in his massive The Artist's Studio, a Real Allegory Summing up Seven Years of my Artistic and Moral Life, one can find what he did paint: a landscape, a dog, a street urchin. Behind Courbet are the friends and patrons, who supported him, including Charles Baudelaire, the poet and critic, who called for a “painter of modern life.”

Both of these works are bold statements on Courbet’s belief in a different form of realism. Both were rejected from the annual Academy Salon; in response, Courbet erected his own Pavilion of Realism near the Salon. Courbet manufactured such a controversy that hundreds flocked to see the 40 works he exhibited—but sales were disappointing. Courbet became a hero, however, to the next generation of painters as they also sought to paint modern life.

->Galleries 19 and 20

Courbet’s friend Edouard Manet took this idea of realism and modern life one step further, into the city. Manet grew up in Paris and trained at the Academy. Like Courbet, he sought a new modern style, and he took Courbet’s approach one step further, turning his eye on the new Parisian city class. His Luncheon on the Grass was also rejected by the Academy as one of the most scandalous paintings of the1863. Can you see why?

Two men in modern clothes--but the women have no clothes on! Worse still, the central women is looking back! But what was most shocking –all the mistakes the painter made. Can you find them? Manet was the first painter to say that a painting didn’t have to be perfect: it was the artist’s subjective idea of reality, not reality itself, that was important.

Manet, Olympia 1863

Manet scandalized Paris even further with his Olympia. Cartoonists lampooned the work, and pregnant women were warned to refrain from viewing such pictures. The impertinent gaze of the woman was unlike any nude seen in painting before—with shoes and a choker that clearly indicated she was a prostitute. Look carefully and you’ll see the typical inconsistencies of Manet, asserting his right to paint what he wanted, as he wanted. Think about Bougereau’s Venus, done the same year, and you’ll see just how far Manet deviated from the norm

Strolling through these galleries, you’ll find the friends who gathered at the cafes and dance halls. Manet’s sister-in-law Berthe Morisot (seated) and other friends make an appearance in Le Balcone . The writer Emile Zola is seated with his collection of Japanese art and Olympia in the background. Manet as well as other artists were also interested in showing the loneliness and isolation of the new modern city, especially those workers that had left their families behind, or displaced by the new boulevards that mowed through poor neighborhoods.

Manet: Le Balcone 1868 & Portrait of Emile Zola 1868

->The hallway gallery that runs parallel to the side galleries is a Who’s Who of Parisian artists and friends that gathered in cafes and studios. Gustave Caillebotte’s Floor-Scrapers, who are laboriously cleaning the floors of those magnificent new French apartments, show backbreaking work in a golden light. Caillebotte was not just a painter following the in footsteps of Manet; he was also the organizer of several Impressionist exhibitions and a generous patron of his fellow artists. In fact, the circle of modernists was small enough that they collaborated, shared studio space and stepped into each other’s paintings on a regular basis. Frederic Bazille painted his own studio in 1870, complete with Manet (who actually painted the Bazille at the center) and Renoir, his studio-mate.

Caillebotte, The Floor Scrapers 1875 & Bazille, Bazille's Studio 1870

And Manet himself stands at the center of his studio in Henri Fantin-Latour’s Studio at Batignolles , painting a lesson surrounded by his fellow painters, including Baudelaire and Bazille. Can you guess which are Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir? They are dressed not in the suits of gentlemen, but the working-class clothes of a laborer—a new generation of painters that would push the limits of modernism even further.

Impressionism

->The upper galleries celebrate the Impressionists under flood of sunlight coming through the skylights—they are meant to be viewed as they were painted, in natural light. The Orsay has such an excess of Impressionist riches, you can stroll through the galleries like a 19th century boulevardier and stop in front of those you like.

Monet and Renoir were not independently wealthy like the other artists. They came to study in Paris and learned from Manet, but took modernism in a different direction. Find Claude Monet’s Picnic in the Park and you’ll see the difference between Manet and Monet. Manet critiqued modern life while Monet celebrated it. At Monet’s picnic, a group of artists in the park (including Courbet and Bazille), are dressed in their best, sunlight dappling the blanket and people. The women are dressed in their best (not nude!), with full skirts that fill the foreground. The men, too are dressed in contemporary clothing, putting the picture clearly in the present day. Monet was not interested in confronting society; he wanted to enjoy it.

And Monet painted it as it happened. Using brand-new tubes of paint that could be transported outdoors, he dabbed strokes of pure color (cobalt and violet) on an unprepped canvas. This accounts for the immediacy of the color and quick brushstrokes. If you’re wondering why Picnic in the Park is cut into pieces, when Monet was struggling to pay his rent he offered the canvas to his landlord in lieu of payment. When the artist returned for his canvas years later, mold had destroyed sections of the canvas, so he cut it into 3 pieces—here are 2 of them. His poverty didn’t last for long, however…

The first Impressionist Exhibition, held in 1872 was an immediate success: the newly wealthy middle class loved seeing themselves enjoying Paris and all its new attractions and avidly bought these paintings, which were much more affordable than the larger history paintings bought by the aristocracy. The term Impressionism comes from that first show—a critic walking through, commented that the works were not finished paintings, they were mere “impressions,” and the name stuck. The flip comment captured the transitory nature of the paintings and modern life. The Impressionists (above all Monet) sought to capture the quick optical impression: how something looked at a moment in time, rather than for eternity.

Monet: Cocquelicots (poppies) 1873

Look closely at Cocquelicots, which shows Monet’s wife and eldest son in a field of poppies. The dabs (“taches”) of orange-red pigment don’t make sense, but step back and you’ll see the scene resolve before you. Cezanne said “Monet was just an eye, but oh what an eye!” All of his landscapes are filled with flowers, his cityscapes filled with people, all enjoying the hustle and bustle of city life, captured in a quick impression.

One of the few exceptions is the portrait of his wife, Camille on Deathbed. Here it is not merely the optical impression, but absolute grief which streaks across the canvas. The tortured swaths of paint are a precursor to the emotional expressionism of Vincent Van Gogh just a decade later.

Camille on Deathbed 1879

Monet often painted the same scene repeatedly. He was interested in the quick optical impression—of a haystack, cathedral, poplar, or train station, like the Gare St. Lazare as it changed with the effects of steam, smoke, changing light. Not how something remained the same, but how it changed: the optical sensation of an image. One wall shows his predilection for motifs: 4 different versions of Rouen Cathedral (he painted it over 30 times).

Monet: Rouen Cathedrals 1892-94

In his garden at Giverny, Monet had a specially made canvas holder so he could work on canvases according to the time of day; as the light changed, he would change the canvas. Which do you think was done when he was older and couldn’t see as well? Hundreds of Monet’s waterlilies are scattered around the world today, though the largest and most exquisite, a series of 2 rooms that immerse you in Monet’s pond, are at L’Orangerie, across the Seine.

Monet: Lily Pond, Green Harmony 1899, Water Lily Pond, Symphony in Rose 1899, Blue Water Lilies 1916-1919

Auguste Renoir was Monet’s painting partner—but he was much more interested in the effects of light on people. In paintings like Dance at the Moulin de la Galette (1876), the workers are always in their best, and you can see the sunlight as it dapples the faces of the dancers. To our eyes, they are elegant figures; to the eyes of Renoir’s audience, they were wage workers dressed up for the night (the straw boaters of the men are the tell). But no matter—they clearly know how to have fun, and enjoy themselves, leaning in to talk, flirting with a smile, or embracing in a dance.

Renoir: Dance at the Moulin de la Galette, 1876

Compare Danse a la Ville to Danse a la Campagne to see the class differences: in the city, the couple in formal attire seem stately and still, while in the country, the woman with her hat and fan is caught mid-turn, the pleasure of the moment (or whatever her partner seems to be whispering in her ear) clearly on her face.

Danse a la Ville with Danse a la Campagne, 1883

In his later years, Renoir left Paris, but continued to paint women (and often his sons) in the sunlight of the Mediterranean. His later nudes have a classical, monumental quality. Dressed only in sunlight, they fill the frame with “taches” of russet, cream, green and blue.

Camille Pissarro was the oldest of the Impressionists, and the only one to have exhibited in all 8 Impressionist Exhibitions. Closer to the age of Manet, he started his career in the countryside, with Corot, and is considered one of France’s premiere landscape painters. After meeting Monet and Renoir, his painting became less naturalistic and more impressionistic; look at how many of his works show the effects of light, snow or rain on a scene.

Pissarro, The Seine and the Louvre 1903

Most are of the countryside near his home, but The Seine and the Louvre captures the effects of fog as it creeps across the Pont des Arts. In the 1870-72 Franco-Prussian war, roughly 1,500 paintings were destroyed by Prussian soldiers when they occupied his home (some were reportedly used as doormats). He produced another 1000 or more scenes of Paris and the countryside during his career; the Orsay has 50+ paintings.

Pissarro is important not just as a painter, but also as a constant unifying force among the disparate artists. He was an important champion of later Post-Impressionists like Cezanne, Seurat, Gaugin and Van Gogh. Self-Portrait shows Pissarro with his long beard and laborer’s coat, painting studies behind him, exactly as he must have appeared to those he mentored.

Pissarro, Self Portrait 1873

Edgar Degas’ dancers have some of the same luscious coloring of Renoir’s nudes, although his outlook was totally different. He was closer in age to Manet, and considered himself a Realist like Manet. In a Cafe echoes Manet in the palpable isolation of the two drinkers—side by side, yet drinking alone. The woman's glass of green-ray absinthe was 75% alcohol, with a wormwood neurotoxin that literally drove drinkers insane.

Degas: In a Cafe (L'Absinthe) 1875-76 & The Ballet Class 1871-74

The Ballet Class displays the plunging perspective typical of Degas. At first glance, you’re taken in by the tulle and ribbons of the dancers as they listen to the dance master. But look closely—the closest girls are young and awkward, the dancer on the left scratches her back, while the dancer in the far distance makes a face. At the time, ballet dancers were not glamorous, but actually very poor, called “dance rats.” Even so, he makes them beautiful.

Degas also liked to experiment. His pastels on canvas are extraordinary in their coloring and striking in composition. In L'Etoile, a dancer bows, her tulle blooming around her in contrast to the blurred line of dancers behind.

Degas, L'Etoile 1878

Little Dancer steps from the canvas onto a pedestal, one of the few sculptures done by Degas (or any of the Impressionists/Realists). Degas added to the striking realism of the saucy adolescent’s pose with an actual dance corset and tulle skirt, real hair covered in wax, and a pink satin ribbon for her braid.

Degas: Little Dancer 1879-81, X-Ray of Little Dancer

Degas' dancer was Marie van Goethem, the daughter of a laundress and a member of the Paris Opera ballet corps who disappeared from history after leaving the dance corps in 1882 (most of the dancers were required to entertain paying gentlemen backstage, and often became prostitutes after aging out of the corps). But she lives on—in multiple castings of Degas’ original wax and clay model, children’s books and even a play. She was x-rayed in 2014 and the results were surprising: lead pipe, rope, even paintbrushes were used to build up the core armature, which was covered with clay, then fired.

Berthe Morisot and her sister were students of Corot, and Berthe married Manet’s brother Eduoard. In addition to his Balcony (above), she appears in a portrait by Manet. The Cradle is painted with vigorous impressionistic brushstrokes that give the painting a three-dimensional effect. Gaze at the work of these female painters and their spaces do come into focus: domestic scenes, or public parks and theatres where “respectable” women could go. Typically, the women look down demurely and do not acknowledge the viewer.

Morisot, The Cradle 1872 Gonzales, A Loge at the Theatre des Italiens 1878

Eva Gonzales was the only student of Manet; you can see his influence in the sharply defined features of her women who, like Morisot’s, are confined to specific spaces like the nursery or park. A Loge at Theatre des Italiens displays another subject of Impressionists: women on display at the opera. Her work is unusual (and was seen as scandalous at the time) because the woman, leaning forward to emphasize her décolletage, is staring back! This is where you see the influence of Manet most clearly.

Female Impressionists did not have a “feminine” style, but the spaces they depicted were quite different. The nudes and dancers which grace so many artist’s canvases were paid models or friends, without the “respectability” of the moneyed class. Many of the female Impressionists were part of that moneyed class, and therefore much more restricted in the public places they could visit.

The American Mary Cassatt moved to Paris from Philadelphia. As a painting partner of Degas, she shared his interest in Japanese prints with their flat colors and angular lines. Unlike Degas, she wasn’t allowed out in public on her own to visit dance halls and ballet rehearsals. Like Gonzales, she painted women at the opera, though the Orsay’s collection of her works consists of a Girl in Garden and mothers with children.

Cassat: Girl in Garden 1880-82 Mother and Infant on a Green Background 1897

Cassatt never married, but was close to her siblings and their families, who also lived in Paris. The beautiful intimacy with which she portrays children, and especially children and mothers, is unparalleled. Look closely, and you’ll recognize the influence of Degas in the sharply defined features against the whirl of whitened brushstrokes.

->The Terrasse Seine, a 2nd floor sculpture gallery on the street side of the museum, overlooks the crowds below. It can be accessed by the stairwells at either end of the building.

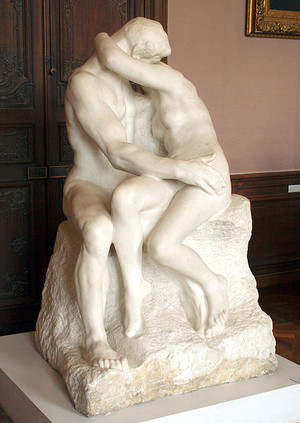

Auguste Rodin and other modern sculptors who socialized with the Impressionists are perched on the 2nd floor sculpture galleries, basking in the natural light.

Rodin, model of The Gates of Hell 1917

You might not recognize Auguste Rodin's The Gates of Hell, but you might recognize elements of it. Rodin was originally commissioned to create a set of monumental doors for a new decorative arts museum in Paris. He conceived the Gates of Hell as a complement to the Gates of Paradise designed by Michelangelo for the Florence Cathedral. Although the museum was never built, Rodin worked on models for his vision of hell throughout his long career. See if you can find The Thinker and The Kiss—both are more famous as independent sculptures. “What makes my thinker think is that he thinks not only with the brain, with his knitted brow, his distended nostrils and compressed lips, but with every muscle of his arms, back and legs, with his clenched fists and gripping toes.” Rodin seemed to specialize in figures driven by passion. And it's fitting that this plaster model is here at the Musee d'Orsay, where the museum of decorative arts was intended.

->Galerie Francoise Chachin is the open sculpture gallery on the opposing side, accessed through the stairwell closest to the entrance

There, you'll find Rodin's portraits of Victor Hugo and Honore Balzac. Hugo, famous for writing the literary classics Seminal, Les Miserables and Notre Dame de Paris, was already a cultural institution at the time, and sick of portraits. Rodin was forced to observe him from a corner or on the porch. The busts are cast from several studies Rodin made, oversize pieces befitting such a literary giant.

Rodin: Victor Hugo 1883, Honore Balzac, 1891-97

The best example of Impressionist sculpture would be the plaster cast of Balzac in his bathrobe. Rodin, a close friend of Renoir, was interested in translating the immediacy of modern life to bronze. His portrait of the writer Balzac, who preferred to write in his dressing gown, was seen as so informal and unbecoming that the commission taken away from him. Yet he captured the spirit of the author—and the bronze now stands proudly (haughtily?) in the center of the gallery. You'll find an entire room of Rodin's studies, as well as the final versions of his monuments at the Musee Rodin just a few blocks away, near Les Invalides.

Rodin: La Pensee 1886 and The Kiss 1882 Claudel: Sakountala 1905

Passion defines the work of Rodin’s protégé and partner, who is just gaining attention in her own right today: Camille Claudel. Claudel came from a wealthy family of intellectuals; her brother Paul was a well-known poet and writer. Claudel’s father supported her interest in sculpting, and she worked as an assistant in Rodin’s studio. Eventually, she became romantically involved with him. Rodin’s La Pensee (1886) is a portrait of Camille, encased (or imprisoned?) in a block of unfinished stone. By this time, Claudel had her own studio, though their relationship continued, in some form until 1899. Her skill matches that of Rodin: compare his Kiss from the Rodin Museum) to her Sakountala, based on an Indian story, and the differences in style and technique are almost imperceptible. One could argue her work is more dramatic, or even expressionistic, when you look at work like Clotho, one of the Three Fates, usually shown as old and haggard, draped in the thread of human life she spins for eternity.

Claudel: Clotho 1893 and The Mature Age 1905

Fate was not kind to Camille Claudel.The Mature Age is a portrait of herself as a woman beseeching an aged man whom Time is escorting away. The attenuated forms and agitated surface are typical of both sculptors. But such raw emotion was seen as unseemly for women. Her brother Paul observed that the sculpture showed "My sister Camille, Imploring, humiliated, on her knees, that superb, proud creature, and what is being wrenched from her, right there before your very eyes, is her soul." But it was Paul who finished the job. After the death of their father in 1913, Camille was institutionalized 8 days later--against her wishes and the advice of her doctors—for the next 30 years! She never sculpted again, and was visited only seven times by her brother in all that time (her mother never visited)

Claudel's work, however, now stands proudly sided by side Rodin in many major collections, including at the Musee Rodin and since, 2017, her own museum in her hometown of Nogent-sur-Seine, just outside Paris.

Pompon, White Bear 1922

Amongst the figures in various poses, all heirs to Rodin and Claudel, you’ll find Francois Pompon’s White Bear, one of the most popular artworks in the museum—you can find various versions of it, from key chains to mousepads, in the gift shop. Maybe that’s because it has a modern abstraction that we can easily appreciate. Pompon himself worked as an assistant to both Rodin and Claudel before starting his own studio, and gained inspiration by visiting the Paris Jardin des Animaux. The 5 foot stone bear is a product of not just the early modernists found in the museum, but also heavily influenced by the abstract modernism of later artists like Picasso and Matisse (which you can find at the Musee of Modern Art at the Centre Pompidou). Little did Pompon know how the polar bear would become a symbol of climate change a century later!

Post-Impressionism

->On the third floor closest to the skylight are the Post-Impressionists, the fin de siècle artists that summed up the new modern world as it raced towards the 20th century. Begin on the entrance side and you can visit Toulouse-Lautrec, Seurat, Cezanne and others (see below), or turn to your right to visit Van Gogh and Gaugin (see further down).

The Post-Impressionists did not have a single uniform style. A very disparate group of artists, they shared the common experience of living in Paris and even exhibiting with the Impressionists. But rather than a quick impression, they were interested in building on the lessons of Impressionism in a variety of ways.

Georges Seurat took the quick brushstrokes of pure color and used color theory to place each point of color surrounded by its complementary color—what Felix Feneon called Neo-Impressionism (or pointillism).

Seurat, The Circus 1890

Seurat was influenced by the color theories of Chevreul, who proposed that a color is brightest when next to its complementary color on the color wheel, scienticized Impressionists by reducing each stroke to a dot, surrounded by its complementary color.

Up close, a stroke of indigo is made more vibrant by the smaller dots of orange surrounding it. Further back, however, this painstaking technique of pointillism, gives an overall effect of modulated and monumental forms. Look closely at Circus, his last work and you will find that no one speaks or interacts; they all exist in their own separate sphere of colored dots. Pay attention to the frame as well: Seurat carefully painted the frame in vivid indigo to set off the colors of his canvas.

There are just a few examples of Seurat—the process of pointillism was very slow, and Seurat died young. But you can see the mind of the artist—in the form of his studies for larger works like Sunday Afternoon at the Grand Jatte (in Chicago) and The Bathers (in London). The landscapes by Seurat are almost a concretization of Impressionism in the methodical placement of brushstrokes, each one accompanied by its complement. And the figures are small snapshots of the more famous works as Seurat works out the color harmonies for each one.

Toulouse-Lautrec: Jane Avril Dancing 1892

Henri-Toulouse-Lautrec certainly enjoyed modern life. An aristocrat born with a short leg, he seemed to feel most at home in the dance halls, with the drinkers and dancers of Parisian night life, like Jane Avril Dancing. While he shared the same subject with the Impressionists, his style is quite distinct. The flat colors and sinuous lines recall the Japanese prints he avidly collected and the Art Nouveau style of fin de siècle Paris. Like Degas, he added glamor to the hard work of dancers: “Everywhere and always ugliness has its beautiful aspects; it is thrilling to discover them where nobody else has noticed them.” Many of the most famous dancers, like La Goulue and Jane Avril, worked well into their forties! Toulouse-Lautrec, a friend of both women, was actually one of the first artists to use new automated printing technology for his lithographic posters that are now synonymous with fin de siecle Paris: Moulin Rouge, Jane Avril, Le Chat Noir can be found on towels, trays, postcards, cups, umbrellas and other assorted objects in any store in Paris.

Cezanne, Still Life with Apples 1880-84

While Seurat and Toulouse-Lautrec had the city as their subject, other Post-Impressionists escaped it. Paul Cezanne, born in Aix-en-Provence, lived in Paris for a few years and exhibited with the Impressionists, but eventually returned back to his southern home. Note the dates of Paul Cezanne’s Still Life with Apples. Cezanne was interested not in the optical impression, but in the essence of an object—what always remains the same (that’s why it took 4 years to create one still life!). He told his friend Emile Bernard, “I want to make of Impressionism something solid and lasting, like the art in museums. To get to this, he worked and reworked his subjects, sometimes over a period of years. The Impressionistic, sketchy brushstrokes become patches (taches) of color, with heavy contour lines that simplify and abstract the forms. He even tilts the picture plane up so you can see the totality of forms.

In one of Cezanne's 30+ versions of Mont Sainte Victoire the pine trees give way to carefully arranged fields of color that lead to the mountain. He liked to paint the mountain because it never changed, but he could change it every time. Even the Bathers conform to Cezanne’s geometry, as each of the outer figures lean into his triangular composition. Because of that abstraction, he was the most important artist for later painters like Matisse and Picasso; both artists created their own versions of the Bathers in homage to Cezanne.

Cezanne: Mont Sainte- Victoire 1890, Bathers 1890

The Cezanne gallery contains many portraits, which is surprising, given the artist's penchant for re-working canvases. In one case, he required over 80 sittings! Even his self-portraits become a mosaic of patches which emphasize the underlying structure of his face.

Cezanne, Self-Portrait 1875

Even more striking is his portrait of Achille Emperaire, a fellow painter from Aix. Emperaire overcame the challenges of being a little person and a hunchback and was well respected by all the painters of his generation. In the words of Cezanne, whose portrait gave him the fame he lacked in life "Well, he didn't make it. Still, he was a lot more of a painter than all those dripping with medals and honours.”

Cezanne, Achille Emperaire 1868

-> Follow the crowds to find Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gaugin tucked into the corners of the top floor, just above the entrance.

Post-Impressionism: Expressionism

Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gaugin both longed for a life beyond Paris, and both revolutionized color as an instrument of emotion.

Van Gogh only took up painting in 1881. His early works show a sympathy for the working class, but his stay in Paris is where his vision was fully formed. Working with Toulouse-Lautrec, Seurat and others, he took the impressionist brushstroke and imbued it with palapable emotion in textured brushstrokes and vivid colors, each one with its own meaning. He wrote over 750 letters to his brother Theo, detailing his artistic philosophy, perhaps because it was his brother who supported him (and no, he never sold a painting in his lifetime). Each color had a specific emotional meaning for him.

Van Gogh, Self-Portrait, 1889

Blue, for example, was the color of happiness. His Self-Portrait from 1889 shows his contentment, yet the portrait is still swirling with his telltale brushstrokes (sometimes actually laid on with a palette knife instead of a brush).

Van Gogh:"L'Arlésienne 1888, Dr. Gachet 1890

Van Gogh was clearly wracked with emotional instability all of his adult life; stories and theories about him range from lead paint-induced poisoning, psychotic episodes, and syphilis. Though we don’t know what tormented him, we empathize with his pain and see the emotions in the paint, often so thick it was laid on with a palette knife. It’s that emotional connection he made with colors and his subjects which make his work so relatable today. All the figures from his life come to life on the canvasses: L’Arlesienne at the bar where he drank (apparently way too much), and Dr. Gachet, who treated him (Gachet’s collection of French artists, donated by his family, is in the downstairs gallery).

Paintings with blue as the key note are meant to convey his contentment. Starry Night on the Rhone was painted a short distance from his rented room. It shares the same sense of peace with its more famous namesake (at MOMA in New York). Glance across the gallery and you’ll immediately get a sense of Van Gogh’s emotional temperature with each painting.

Van Gogh: Starry Night on the Rhone 1888

Compare that to the anxiety of Dance Hall at Arles, crowded with anonymous figures, their dark clothing offset by sickly green accents and ghostly mask-like faces. The only respite in the wall of people is Madame Moulin on the right, who herself looks horrified at being in such a frightful place.

Van Gogh, Dance Hall at Arles, 1888

In these galleries, you can also compare the humble earnestness of Van Gogh to his friend Gaugin, to see just how different they were. In fact, there are some theories that suggest it was Gaugin that accidentally cut off that bit of Van Gogh’s ear. In some ways, Gaugin is the inverse of Van Gogh. While Van Gogh’s paintings are beloved because they show his inner turmoil, Gaugin’s works are still wildly popular today precisely because they so beautifully mask the sordid history of their creation.

Paul Gaugin, too, sought meaning beyond the modern city. He turned first to the women of Breton, in northern coastal France, known for their traditional dress. The sinuous line and saturated color of La Belle Angele do not have the personal emotions of the artist, but the vivid coloring heightens the intensity of the experience for the viewer. The woman, in distinct Breton dress and cap, is inexplicably confined in a circle. While blue was the key note for Van Gogh, intense carmine red is the key note for Gaugin; it stars on the table, bleeds into her dress and suffuses her cheeks. The figure on the left, identified as a pre-Columbian ceramic (Gaugin was born in Peru), foreshadows his turn towards other cultures.

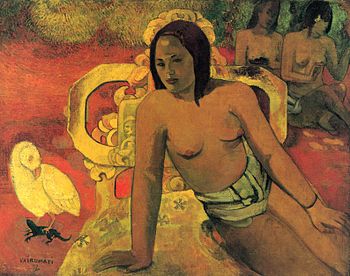

Gaugin worked with Van Gogh in Arles for a short time before leaving for Tahiti in 1891, seeking, as he said “barbarianism, which has been a salvation for me.” For the next 12 years, Gaugin immersed himself in his own vision of an island paradise. His works are not a document of Tahiti—more of his increasingly exoticized and eroticized world.

Gaugin: Tahitian Women on the Beach 1891 Arearea 1891

Compare early Tahitian works to his later ones, and watch the artist undress the women before your eyes. Tahitian Women on the Beach shows Tahitian women modestly dressed. From the same year, Arearea displays a pair of women, their breasts exposed, as part of larger fantasy filled with shimmering red and yellow waters, with semi-nude women worshipping in front of a large statue (a Maori statue from New Zealand blown up to colossal size). These are the types of paintings Gaugin shipped back to Paris, presenting his mythic paradise as reality to the Parisian public.

By the time he created Vairumati in 1897, the clothes were completely stripped off and a Polynesian goddess has become an indigenous Venus, on display for the pleasure of the viewer. The bird with the lizard refers back to the myth of Vairumati and her role as the consort to Ovo, the god of pleasure.

Gaugin: Vairumati 1897 Tehura (Tehe'amana) 1891-93

Gaugin’s personal life seems to have paralleled his paintings The sculpted head of Tehura is a portrait of a 13 year old girl he took as a wife. You can find the sculpture of her head in the galleries, carved and polished like one of the so-called “barbaric knickknacks” sprinkled throughout his paintings for exotic effect. Gaugin spent more time on Tehura’s head than he did on her; he never saw her or the son she bore him after 1893.

Gaugin's entrance to his Hiva Ova (House of Pleasure)

Gaugin continued to “marry” 14 year old girls, interspersed with trips back to Paris for the next few years, until he moved to the Marquesas Islands in 1901. There, he created his Hiva Ova, or “House of Pleasure.” The entrance carved with images of nude women is displayed here as you enter the world of Gaugin’s pleasures. In the case of the Orsay, it perfectly frames The White Horse, another fantasy of Gaugin. An almost incandescent horse laps multi-colored water as another horse moves into the distance. Two natives identified only by their nudity (gender unknown) complete the composition: one on the distant horse, the other crouched in some idea of worship.

Gaugin, The White Horse 1898

With Gaugin, enjoy the beauty, but know the cost. He eventually died of syphilis, but unfortunately infected many of those young Pacific Islanders before he died. It’s up to the viewer to decide if the clear beauty of his works is worth that cost. His women and his children—especially those born in Polynesia, did not see to derive any benefit from association with him.

->Return to the 2nd floor to see how Parisian life changes in Orsay’s collection of decorative arts. Modernism led to an explosion of design in fin de siècle Paris. Art Nouveau (”New Art”), a synthesis of traditional forms and styles with organic elements, dominated French visual and architectural culture at the time. You can quickly (or slowly) stroll through rooms filled with exquisitely curated furniture and accessories. The hallmark of Art Nouveau style: sleek wood and whiplash curves interspersed with intricate ornament.

The two dining options at the Orsay are also impeccably curated.

For a quick bite or drink overlooking the city, you can stop at Café Campana directly behind one of the massive clocks that overlook the city. It’s a bistro style restaurant with a Brazilian Art Deco feel, courtesy of Brazilian designers Fernando and Humberto Campana.

Cafe Campana with clock

If you’d like to return to the Belle Epoch, you can make a reservation at the Hotel D’Orsay, which first opened with the train station in 1900. Most museum visitors miss this because the entrance is separate from the museum entrance. It’s worth a peek to see the formal dining room restored to its original glory: painted ceilings, crystal chandeliers, elegant tables and a menu to match.

More resources:

Interactive map: https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/tools/plan-salle.html